By Brenda Wintrode, Amy DiPierro, Ryan Little, Luciana Perez Uribe, Aneurin Canham-Clyne, Trisha Ahmed, Sean McGoey, Maya Pottiger and Sophia Brown

Published September 2, 2020

Yochebed Israel was just the kind of person Congress had in mind when it voted in March to temporarily ban many evictions across the country as the coronavirus spread.

First, the furnace in her Tampa, Florida, apartment broke, causing her electricity bill to climb above $460 a month for five months, she said. She fell behind on rent, forced to choose between keeping the lights on or paying the landlord.

Then she said she caught COVID-19 from her daughter in April, missing two months of work without full sick pay as a certified nursing assistant at a long-term care center. She had fluid in her lungs. She was tired all the time.

And then, in May, she came home to find an eviction order attached to her door.

“It makes me feel the anxiety of being homeless,” she said.

The federal CARES Act, signed by President Donald Trump March 27, was supposed to protect Israel and people in up to 20 million other rental households from just that fate. It barred landlords whose properties got federal benefits from filing to evict tenants or charging them late fees and court fees for 120 days. Israel lives in a building with a mortgage backed by the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, better known as Freddie Mac. The law should have covered her.

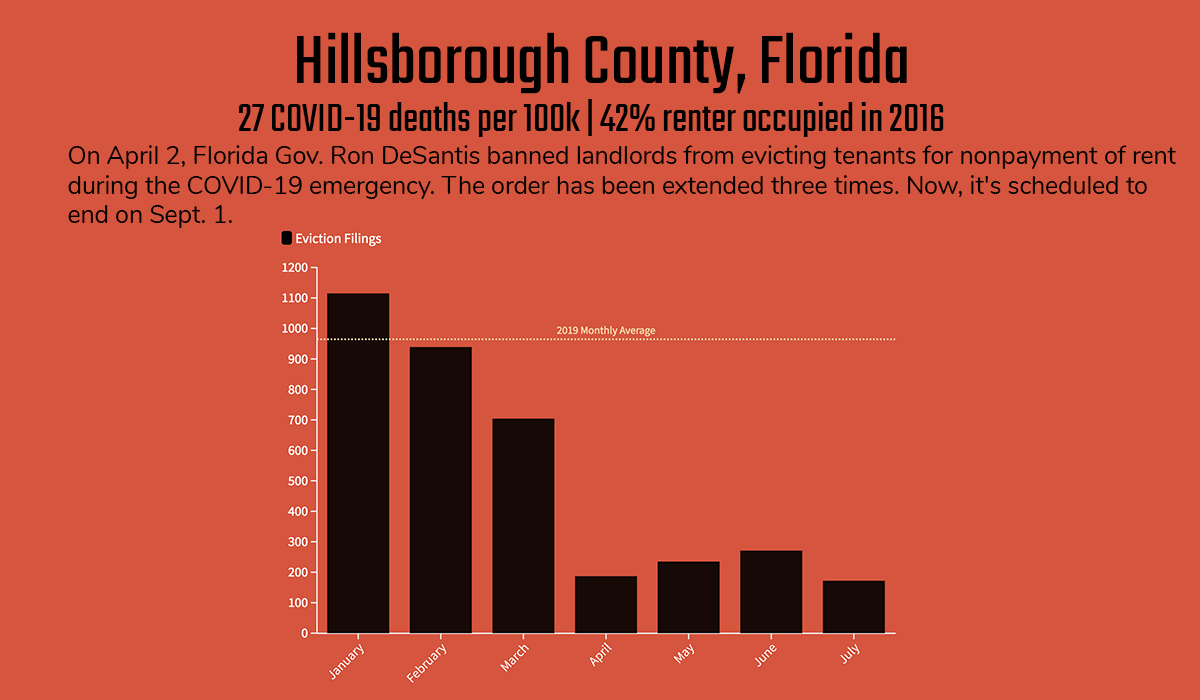

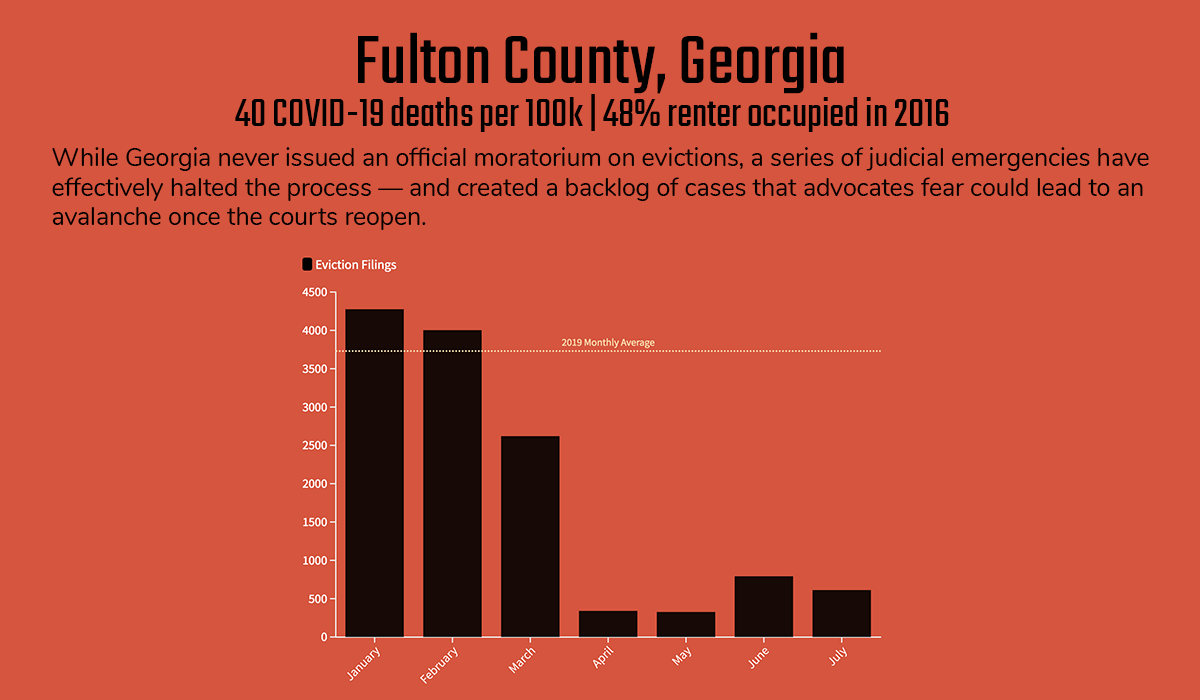

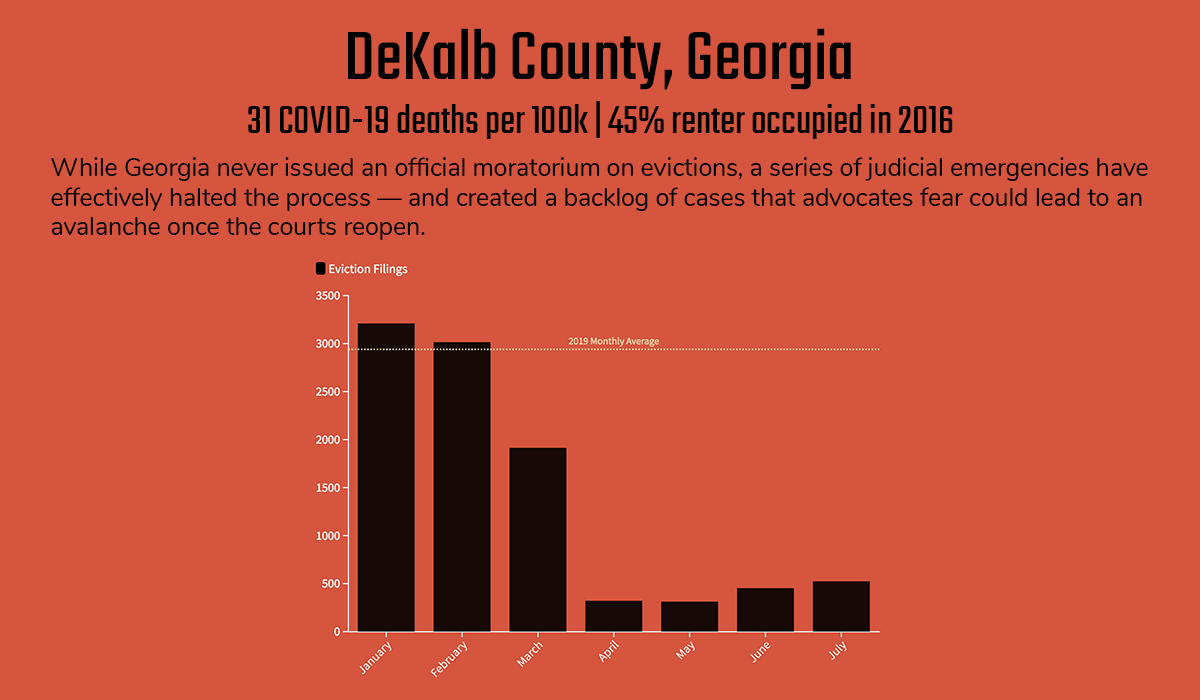

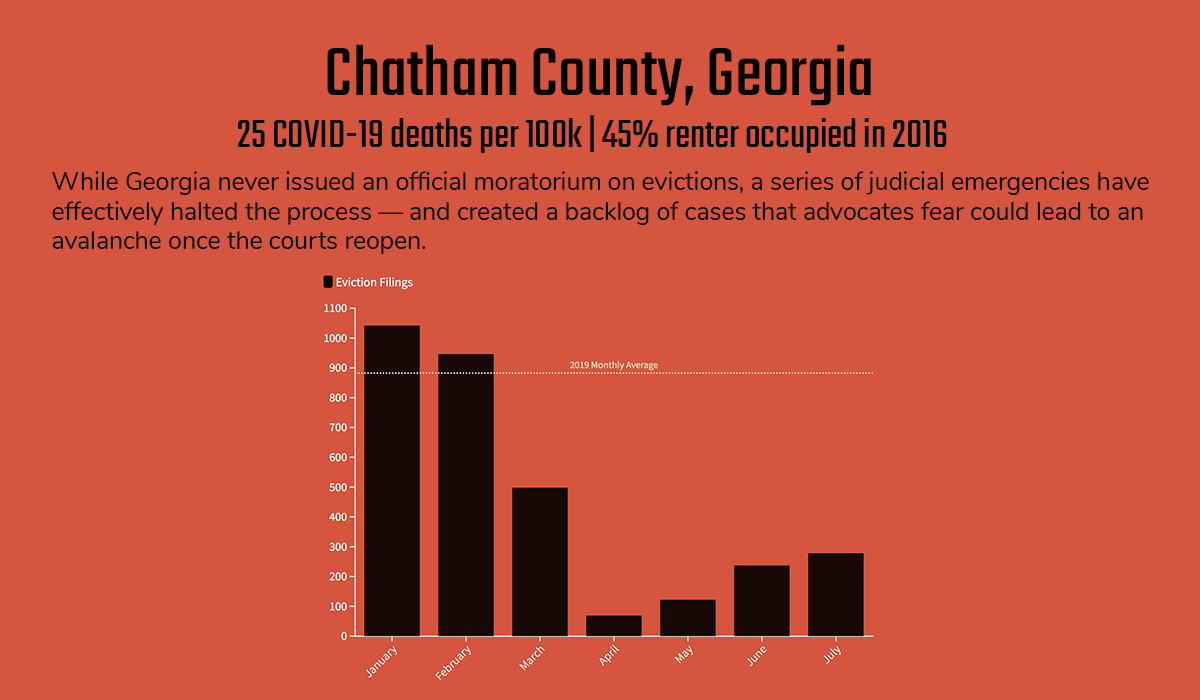

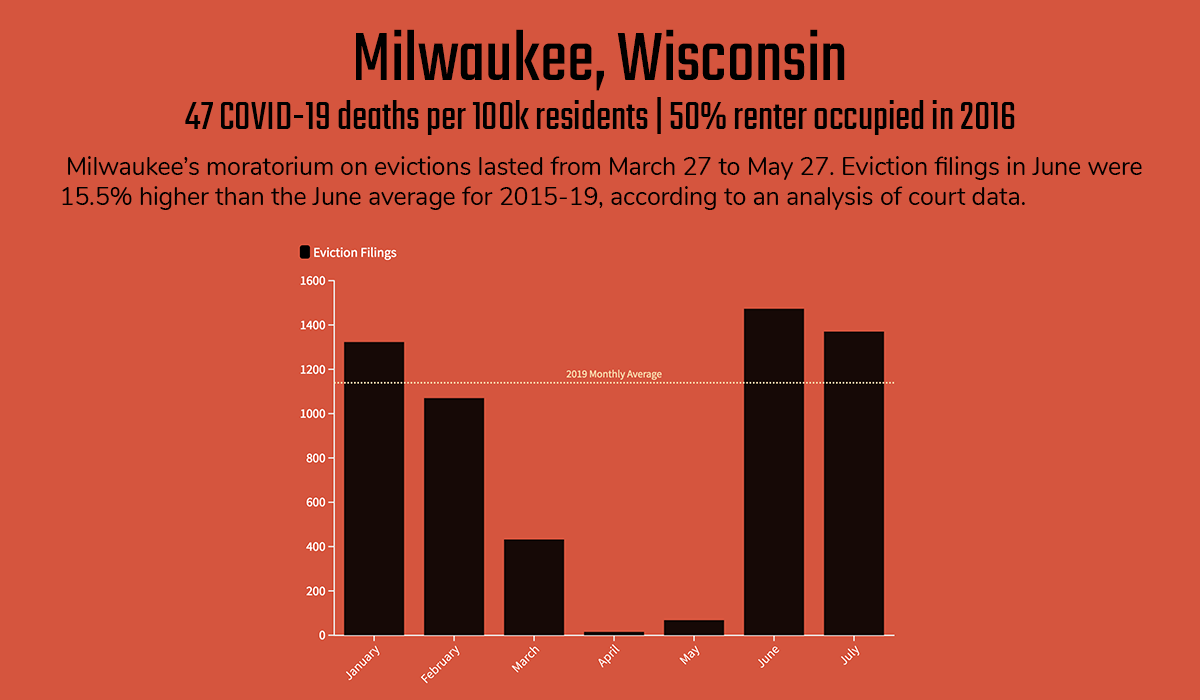

But a two-month investigation by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism found that while the federal and state moratoriums dramatically decreased eviction filings in April and May, cracks in the federal law appeared immediately.

Confusion about the moratorium’s language, which played out in conflicting guidance from federal agencies and the courts, led to selective enforcement. Landlords were expected to determine for themselves if their property was covered by the CARES Act. Renters had virtually no legal help to fight back. And eviction filings in some cities dropped more steeply in white neighborhoods than minority neighborhoods during the federal moratorium.

Israel’s property manager, Tzadik Management, said through a spokesperson that it didn’t know the property in Hillsborough County, Florida, was secured by a federal loan.

It was a “simple miscommunication” between the management company and the ownership of three of the properties it manages, the spokesperson wrote. Court records show Tzadik has since asked the court to dismiss all 24 of the evictions, including Israel’s, that it filed during the federal moratorium.

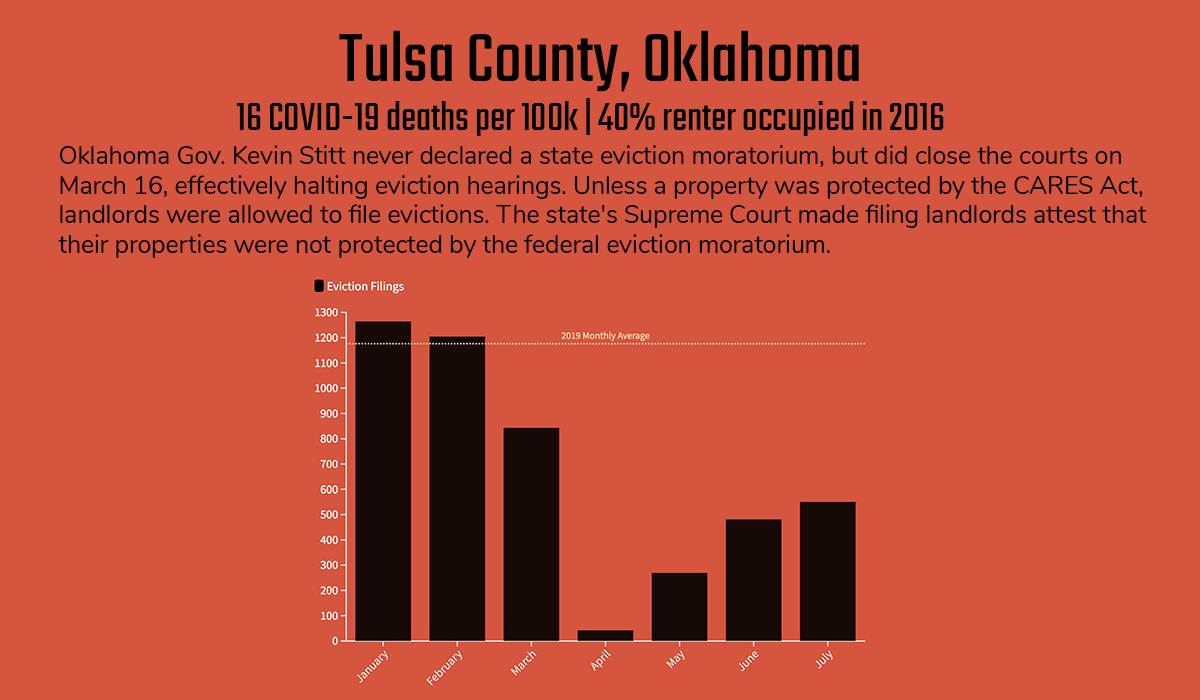

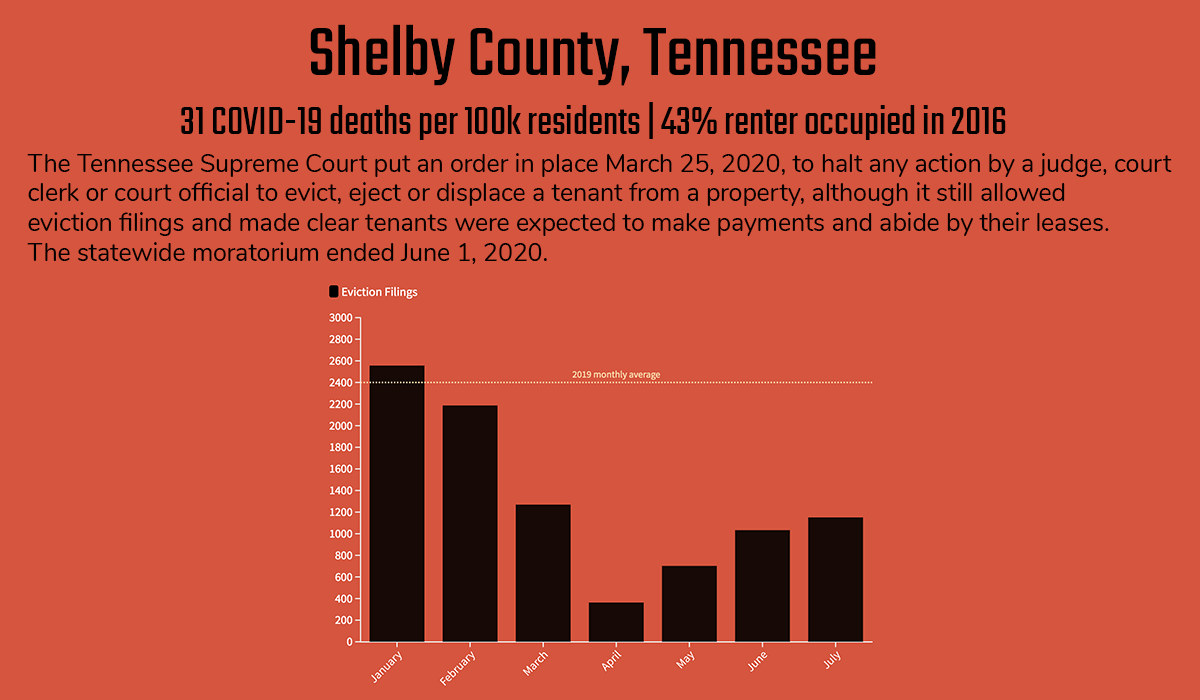

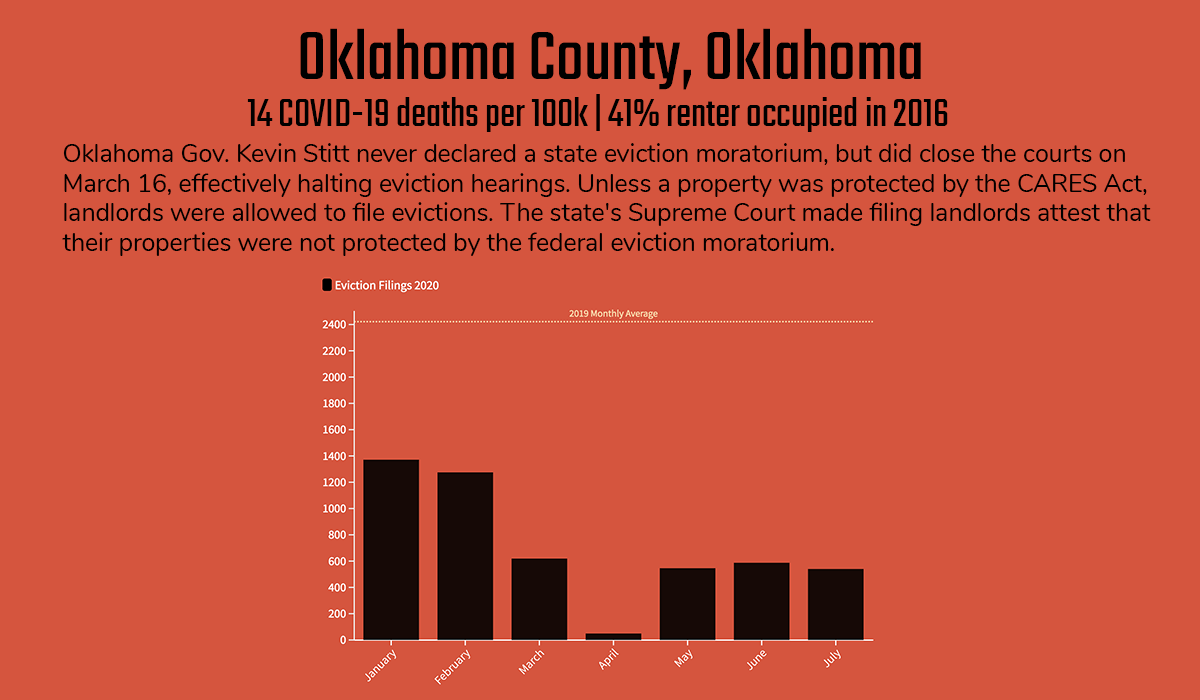

The Howard Center focused on eviction filings in 10 counties that are home to Memphis, Tennessee, Tulsa and Oklahoma City in Oklahoma, Atlanta and Savannah in Georgia, Tampa and St. Petersburg in Florida, New Orleans and Milwaukee — all areas hit hard by the coronavirus. Prior to the pandemic, at least 20% of renters in those counties spent half or more of their income on rent. All also had historic eviction filing rates well above the United States average.

The CARES Act eviction moratorium expired July 24, and the Senate left Washington three weeks later without an agreement with the House to extend it. The Trump administration signaled late Tuesday it will halt evictions for all renters affected by the pandemic through the end of the year as a public health measure to stop the spread of the coronavirus. The moratorium, which does not include money to help tenants in arrears, takes effect Friday, according to a draft in the Federal Register.

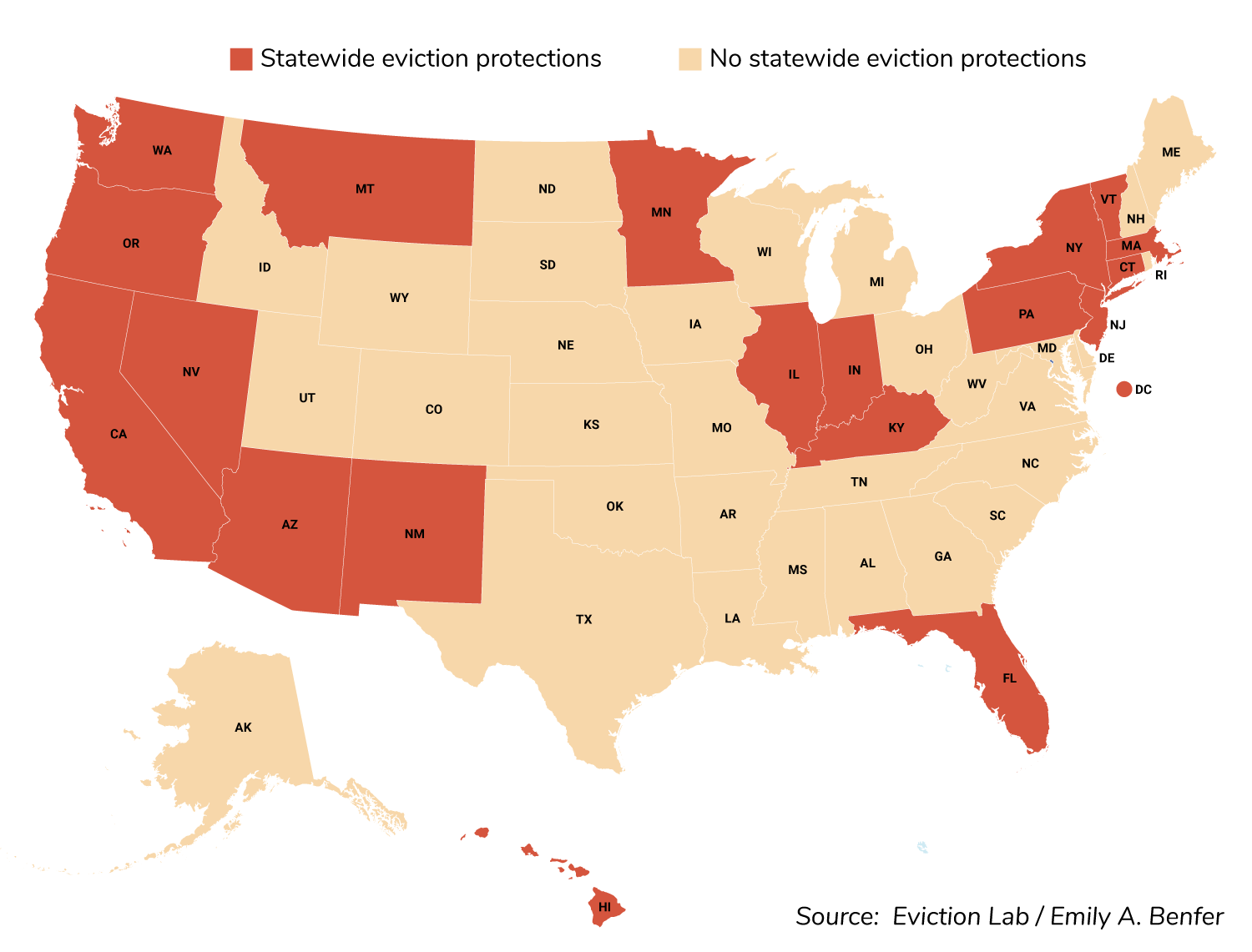

Emily Benfer, a law professor at Wake Forest University and chair of the American Bar Association’s COVID-19 Task Force Committee on Eviction, praised the administration’s action as a “tremendous intervention that promises to protect the health and safety of millions of renters.” But she also warned in an email Tuesday night that it is only a “half measure.”

“Without rental assistance to cover the mounting debt, it only delays eviction and its devastating consequences,” she wrote.

The CARES Act eviction moratorium only covered rentals with mortgages backed by federal programs such as the Federal Housing Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Federal National Mortgage Association, also known as Fannie Mae; properties that received Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, and people who got federal housing assistance, such as vouchers, to help pay the rent.

Eric Dunn, director of litigation for the National Housing Law Project, said Congress should have passed a blanket moratorium in the spring covering all evictions “for any reason.”

“What we got was a moratorium for nonpayment of rent from some housing, which is complicated and difficult to figure out,” he said.

Eviction filings ticked back up in all 10 counties analyzed by the Howard Center in June and July — a pattern evident in 14 of 17 other cities tracked by researchers at Princeton University’s Eviction Lab.

Sources: Howard Center collection of court records, Howard Center analysis of New York Times COVID data, Emily Benfer/Wake Forest, Eviction Lab and U.S. Census.

Confusion on the ground

Landlords and property managers in four of the 10 counties examined by the Howard Center filed at least 101 evictions that violated the federal moratorium, a review of court and other public records found. Courts or plaintiffs since moved to dismiss all of them.

The total is conservative because court data in some counties lacked key details needed to confirm CARES Act violations. In other cases, the Howard Center could not verify information contained in court records.

The CARES Act placed the burden on landlords not to evict tenants in covered properties. In an effort to reinforce that, high courts in Georgia, Oklahoma and Tennessee ordered landlords to sign affidavits saying their property was not covered by the federal law. But even in Georgia and Oklahoma, the Howard Center found wrongful eviction filings kept happening.

Massachusetts and several other states, plus Washington, D.C., have passed statutes temporarily halting evictions, giving Massachusetts tenants some of the strongest protections in the country. But even there, the state Attorney General’s Office said there have been at least 50 eviction cases filed in state court that violated the federal moratorium. The office said all of the cases have now been withdrawn.

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey said in an interview her hope “would be that they would follow both the letter of the law and spirit of the law, which is really to make sure that people aren’t made homeless’’ during the crisis.

But figuring out the letter of the law has not been easy.

The role of federal housing subsidies, such as Section 8 vouchers, is an example. The CARES Act said a landlord could not evict tenants from properties where a landlord accepts subsidies for any portion of the property. But a Department of Housing and Urban Development FAQ said the agency “does not have the authority to extend jurisdiction over unassisted tenants.”

Michael Scaljon is general counsel for Ventron Management, which operates residential properties in Florida and Georgia. He said the company interprets the CARES Act to protect the tenants receiving Section 8 assistance but not their neighbors.

“I believe we have Section 8 housing at Brookside” Park, one of the properties Ventron manages in Atlanta, he said. Court records show 12 evictions for nonpayment of rent were filed there during the term of the CARES Act. “We have not,” he said, “filed against anybody who’s accepting assistance.”

A Nebraska district court reached a different conclusion. In a June ruling, the court rejected the HUD guidance, citing the CARES Act language as “clear and unambiguous” that if one household receives federal assistance then all tenants in the property are protected from eviction.

The court said it believed it was the first in the nation to rule on this issue.

In Florida, two neighboring county clerks differed in their interpretations of the Florida Supreme Court’s order to suspend the issuance of all eviction notices, called writs of possession.

The Pinellas County clerk stopped issuing the writs, but neighboring Hillsborough County did not.

Impact on tenants

All of this confusion increased stress for tenants already under pressure from disappearing jobs — the national unemployment rate soared to a record 14.7% in April and was 10.2% in July. The consequences tenants continue to face from the mere filing of an eviction are real.

Renters often had no way of knowing whether their apartment was covered by the CARES Act, an “inherent drawback” of the law, according to Dunn. The only way to know is to search online databases, some of which only a mortgage holder can access.

Challenging a landlord’s assertion that a property isn’t subject to the CARES Act can be difficult even when a tenant has a lawyer, Dunn said. It’s almost impossible if they don’t.

A Howard Center analysis shows that the vast majority of tenants facing eviction had no legal help.

Yet tenants bear the burden of wrongful filings, even if cases were dismissed by the court.

“Once an eviction is filed, it immediately results in a scarlet E for a tenant or a renter,” Benfer said. “It plummets credit scores and creates barriers to future housing opportunities.”

A New Orleans court dismissed an eviction filing in June against 35-year-old Ernest George because his landlord accepted Section 8 vouchers from other tenants on the property, according to his lawyer. For the ironworker and his family, legal representation and the CARES Act eviction moratorium provided a safety net.

“We’ve been making it. It just got harder and harder when the COVID-19 thing came, and I didn’t get my unemployment right away,” George said.

But unless his case is wiped from court records, the filing could damage George’s credit and could make it harder for him to rent in the future.

Landlord-tenant laws in many of the states examined by the Howard Center favor landlords, who often are legally represented in eviction proceedings. The process from start to finish can take as little as five days in Louisiana, said Hannah Adams, a lawyer with Southeast Louisiana Legal Services.

“Once this ball gets rolling, tenants have almost no time to try to work it out,” she said.

Impact on communities of color

Evictions hit minority communities harder even before the pandemic. George’s majority Black neighborhood in Orleans Parish had an eviction rate five times higher than the national average in 2017, according to a study last year of New Orleans eviction data.

The federal and state moratoriums haven’t closed the gap. The Howard Center found that eviction filings declined more in white neighborhoods than in nonwhite neighborhoods in the Memphis, Atlanta, Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg areas after the federal and state moratoriums were imposed.

In Hillsborough County, home to Tampa, eviction filings dropped 77% in white neighborhoods but 68% in nonwhite neighborhoods after the CARES Act took effect. Pinpointing the reasons for the disparity are difficult.

Census data shows that minority families fell further behind in their rent than white families since the pandemic started. About a third of Black tenants said they missed a rent payment in June compared to 20% of white renters, the data shows.

Impact on landlords

When landlords don’t receive rent, it ripples into the local economy. From the landscaper to the pool cleaner to the plumber, people lose business and income, said Florida property manager Dave Sigler.

“It’s important that these rents get paid,” he said. “Not just to keep the owners having their houses, but it keeps the whole economy going on such a larger scale.”

Landlords did not receive direct assistance from the CARES Act, but their federally backed mortgages were protected from foreclosure. The law provided up to 90 days of forbearance for multifamily properties and as much as a year for properties with four or fewer units.

“I hate filing evictions, I hate putting people out of their homes,” said Paul Howard, whose Florida Landlord Network provides eviction services and tenant screening to landlords throughout the state. “It’s not why I bought rental property.”

To prevent evictions in Memphis, local nonprofits and city officials created a $1.9 million Eviction Settlement Fund for those affected by COVID-19. The funds were not made available until mid-July, and advocates are concerned it won’t be enough.

“We’ve had over 1,000 cases. If each of those settled for $3,000, well, how does it look to you?” said Cindy Ettingoff, CEO of Memphis Area Legal Services.

Officials and nonprofits in Tulsa launched a massive effort in June to pay the rent for anyone who needed help using public donations and unlimited funding from a private donor. If landlords accepted payments from the Landlord Tenant Relief Program, they had to agree not to evict tenants for nonpayment of rent for the next three months. Tenants were required to abide by their lease agreement and pay rent if they could.

But organizers said they provided rent for fewer than 15% of eligible eviction cases. Attorneys for the eviction services companies that handle two-thirds of Tulsa’s evictions said they had warned landlords it was a risk to waive their eviction rights.

Tulsa landlords’ attorney Blaine Frierson said he reminded his clients who were offered the deal they risked not being paid and would not be allowed to evict for about three months.

“The landlord is typically not in a charitable business, and they deserve to be paid,” Frierson said.

What’s next?

Housing experts had warned that the scope of evictions would start to show in September; landlords were supposed to wait 30 days after the federal moratorium expired to file evictions. Trump’s decision to extend and broaden the eviction moratorium could put off that reckoning until January — at least for some.

Ashley Fitzgibbon could be one of them.

The Oklahoma City single mother of six said she thought she was “finally getting it together” before she lost her house cleaning and babysitting jobs at the end of March.

“It was just like such a hard hit,” she said.

Fitzgibbon’s rental house was not covered by the CARES Act and Oklahoma never instituted a statewide eviction moratorium. When the courts reopened in May, her property manager served her with a summons and has done so every month through August.

So far, the 35-year-old has managed to get the cases dismissed by borrowing money, adding a third housemate to the two she already has in the five-bedroom rental house and working odd jobs such as dog sitting to make rent each month.

“I’m so incredibly thankful that there were people that, like, had that safety net, and it sucks that I wasn’t one of them,” Fitzgibbon said.

She’s made the tough decision to sell her 2016 Ford Expedition. The proceeds, she said, will give her a financial buffer through the rest of the year.

And besides, she said she wasn’t using it much anyway. She doesn’t have the money for gas.