By Elisa Posner and Brenda Wintrode

Published July 14, 2020

Twenty-two years ago, the City of Miami signed a landmark consent decree that radically changed the way authorities treated the homeless population.

Before then, city police routinely arrested homeless people for eating and sleeping in public. Authorities destroyed their possessions, in one instance setting fire to them in a park.

Under the agreement, the city began to offer shelter to homeless people rather than jail. City workers were only allowed to destroy a homeless person’s property when it was deemed contaminated or abandoned.

In 2018, the city asked a judge to terminate the decree known as the Pottinger Agreement, arguing Miami had changed its ways and no longer needed court supervision. Last year, the judge agreed, calling the city’s transformation a success story.

But a confrontation this May between Miami police and residents of a homeless encampment has reignited the concerns of homeless advocates that the judge acted prematurely.

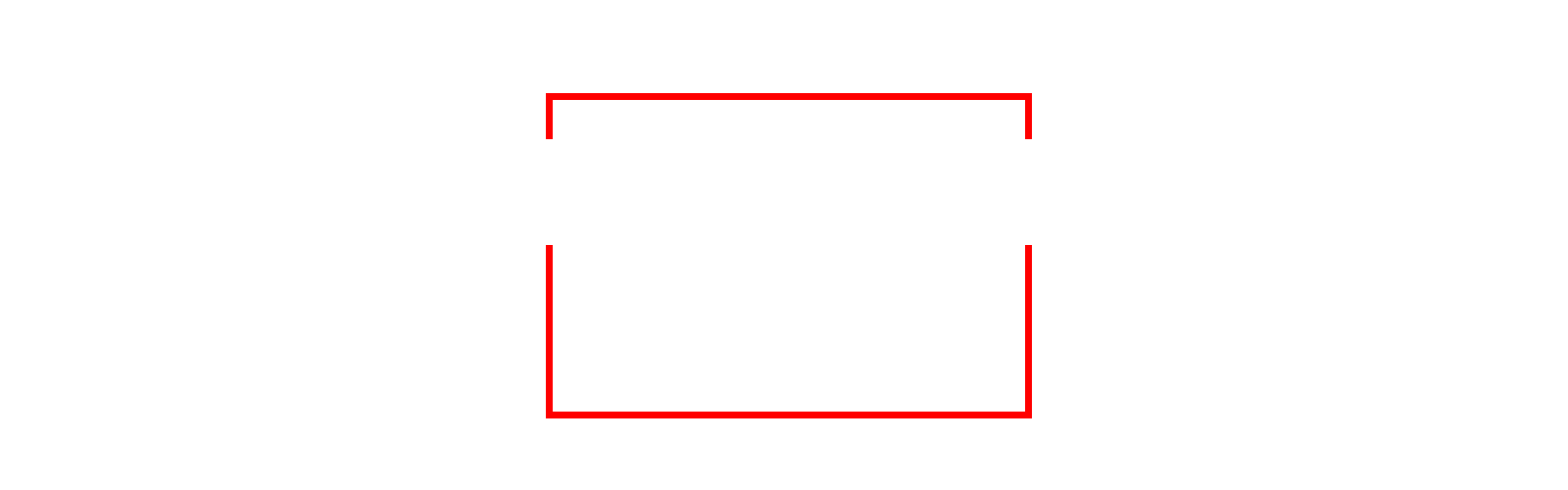

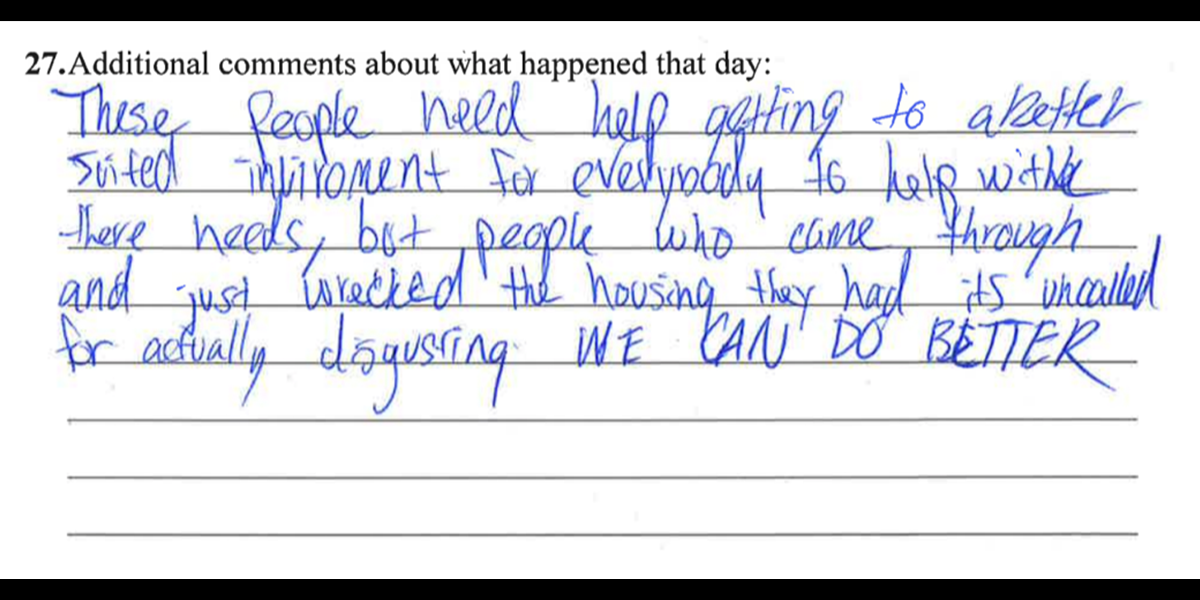

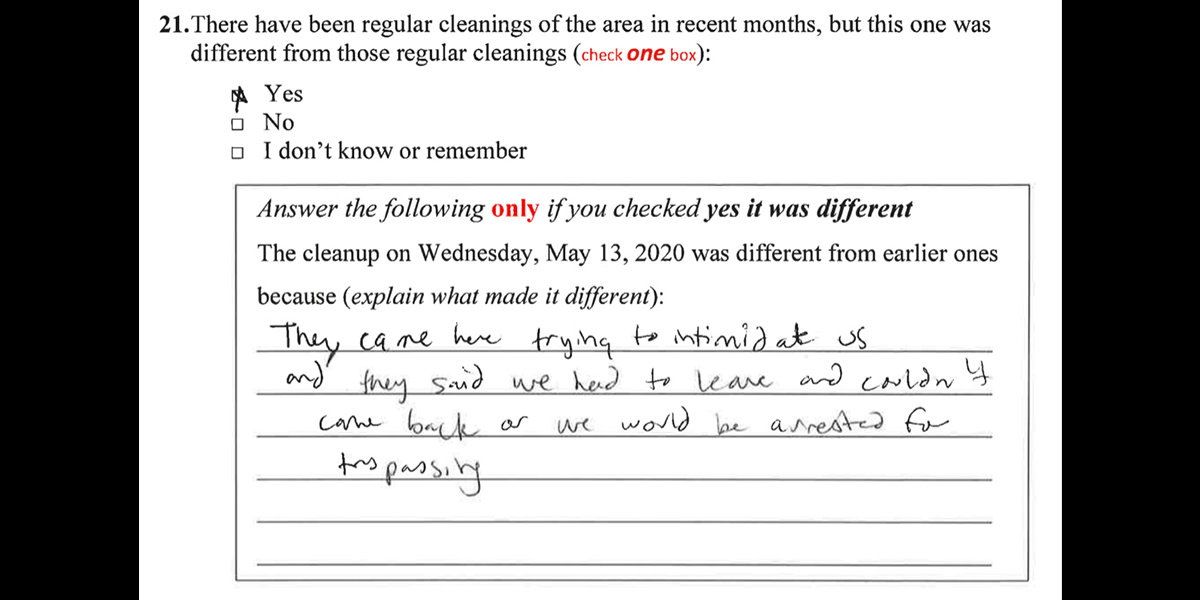

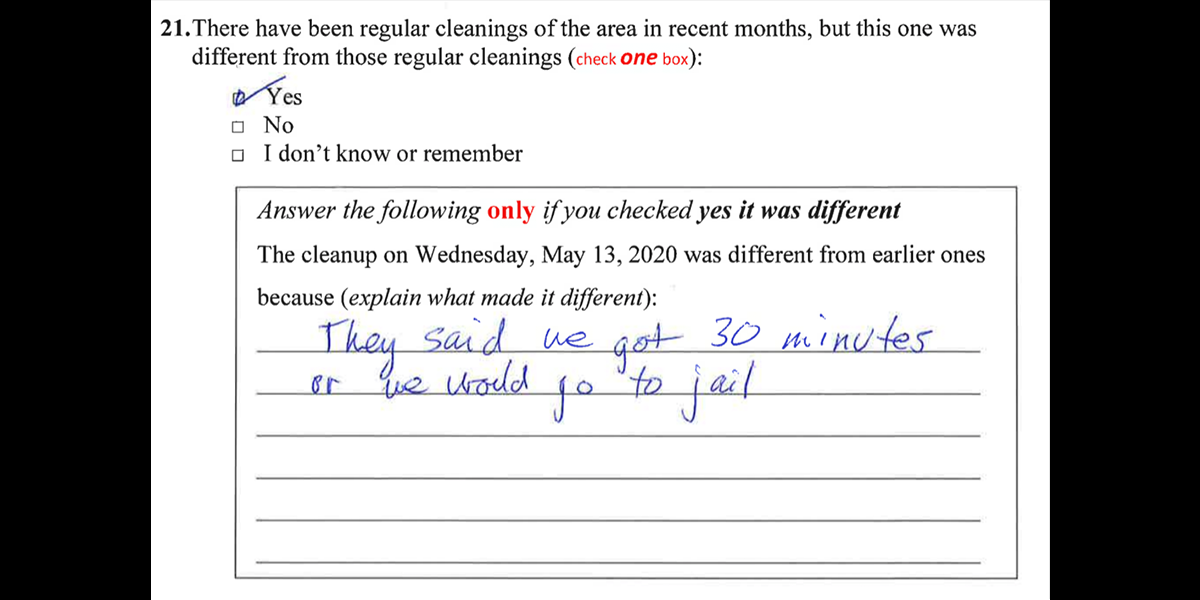

On the morning of May 13, police and city crews gave residents of an Overtown homeless encampment 30 minutes to clear out, according to affidavits encampment residents gave to the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida Greater Miami Chapter.

Jonathan Daniels said he woke to the sound of his neighbors swearing and looked out of his tent to see police cars. City workers were carting away residents’ clothes, shopping carts and barbecue grills.

“It was something out of a movie,” said Daniels in an interview with Howard Consortium reporters.

The crews piled tents, blankets, soap, food and a wheelchair onto the side of the road to be picked up as trash, according to the affidavits. Residents were told they’d be arrested for trespassing if they returned, documents said.

The Miami ACLU condemned the event in a letter to city officials, characterizing it as an “eviction” that left the homeless people traumatized after living there peacefully for months.

City officials maintain it was a routine cleaning. But the affidavits and emails obtained by reporters, along with video taken at the scene, present a much different picture.

They show the city’s action contradicted its own protocol mandating a 7-day notice before cleanings, and federal health guidelines intended to reduce the community spread of COVID-19.

“They don’t care about the people that are inside the city,” Daniels said. “That really was inhumane to me, because everybody has a right to have somewhere to sleep. Everybody has a right to get out of the rain.”

‘We can do better’

More than 600 homeless people lived on the streets of Miami as of 2019, according to the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust. Until last year they were protected by the 1998 consent decree, which limited arrest of homeless people for “life-sustaining” activities, like eating or sleeping in public.

The 1998 consent decree concluded a decade-long federal class-action lawsuit filed by the Miami ACLU and others in the U.S. District Court of the Southern District of Florida.

In 2018, the Miami ACLU asked the court to hold the city in contempt for violating the decree. Thirty-six homeless people testified that police had illegally seized property or harassed them.

The same day, the city petitioned the court to be released from the decree.

City officials assured U.S. District Judge Federico A. Moreno that the 2018 incidents did not violate the agreement. If they were a violation, then it was “unintentional,” the city said. In 2019, Moreno ruled that the city was not in contempt and terminated the consent decree.

The plaintiffs appealed to reinstate the decree. Miami ACLU attorney Stephen Schnably said the May 13 incident mirrored the city’s 2018 behavior and further reinforced their appeal.

The clearing took place in Overtown, a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood that is criss-crossed by an interstate a couple of miles from downtown. For years, dozens of homeless people have lived under the bridge, some along a fence that belongs to the Florida Department of Transportation.

The city’s official version of what happened May 13 is that the FDOT asked the city to assist in dealing with encampments on state property.

But state transportation spokesperson Tish Burgher said it was the city that asked the state for assistance.

Emails provided by the state show the city asked the state to install “no trespass” signs to allow Miami police to enforce them on state property.

The email came from Brandyss Howard, the administrator of Overtown’s Neighborhood Enhancement Team (NET), one of 13 city-run satellite offices tasked with raising the “quality of life” for residents.

“We are seeing a lot of homeless residents along 10th Street and 11th Street in the areas in which we agreed that additional FDOT signage would be posted. This will allow police and our NET team to enforce,” Howard wrote in an email to the state transportation department on April 7.

Howard again emailed the state on May 5 because the signs were still not up. “Because it is on your property we are trying to work to get it cleared but need those signs to be placed there ASAP so police can properly enforce,” she wrote.

The state transportation department posted the “no trespassing” signs on May 12, one day before the city workers and police uprooted the homeless residents.

In an interview, Howard acknowledged that business owners and residents had been complaining to her office about the encampment, but maintains that the emails were in response to a state request for assistance in dealing with the problem.

“In order for us to address or utilize our police to enforce, we would need the trespass signs to be posted by the property owner,” she said.

Nothing was removed from the area unless it was on the sidewalk, she said. She also said “only trash removal” was conducted that day, and that items “deemed debris by solid waste” were the only items taken.

“I physically was not there,” she said. “But I did not instruct, nor did my email instruct, or did I coordinate any removal of any homeless.”

The city is conducting an internal investigation of the incident, she said. But a city spokesperson said Wednesday, “There is no investigation.”

Miami Chief of Police Jorge Colina said the May 13 cleaning was “routine,” and that he was told no homeless person was displaced.

It would be “unacceptable,” he said, if the city were to revert to pre-Pottinger behavior, especially after having been released from the consent decree.

“The criminal justice system isn’t the mechanism to deal with homelessness,” he said.

But Schnably of the Miami ACLU said, “It was much more massive and concentrated than anything that would amount to a cleanup of an area to take away trash.”

The affidavits also contradict the city’s account. Six residents said they were told they would be arrested for trespassing if they returned to the area. One man said a a police officer told him “we had to pack up our stuff and leave, and if you didn’t we’d be arrested.”

“Everyone got frantic,” another wrote.

Five residents reported seeing city workers take the tents belonging to other people and throw them away. One reported his ID, clothes and shoes were taken away; another his soap and hand sanitizer.

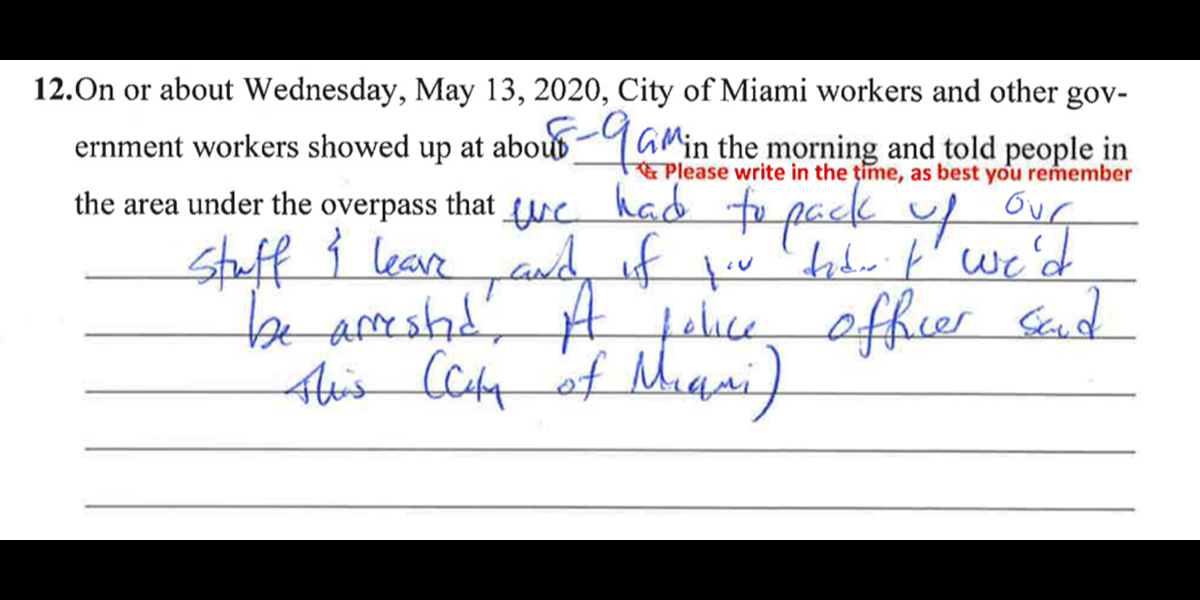

A man, who said he’d become homeless in January, wrote, “These people need help getting to a better suited environment.”

But city workers “came through and just wrecked the housing they had,” he said, adding, “its uncalled for actually disgusting WE CAN DO BETTER”

Lead photo: City of Miami Department of Solid Waste workers use a grapple truck to remove materials from a homeless encampment in Overtown. Courts determined in 1992 that the city was criminalizing “life-sustaining activities” such as sleeping in public and placed the city under a landmark consent decree known as the Pottinger Agreement in 1998, allowing the federal judiciary to monitor the city’s treatment of its homeless population for over 20 years. The decree was lifted last year. (Nailah Summers)