By Nicolle Schorchit, Darryl Kinsey Jr and Patrick Britt

Published January 18, 2021

In the spring of 2013, Holly Hook purchased a mobile home and moved it to Swartz Creek Estates, a manufactured housing community in Swartz Creek, Michigan. At the time, her plan was to become a full-time fiction writer. Knowing her income would remain modest for the foreseeable future, she wanted a comfortable place to live within her financial means.

For the first five years, her plan worked. She paid off the $28,000 bill for her mobile home and the owner of Swartz Creek — a local landlord — raised her monthly lot rent just $20 during that period to about $300.

But in the summer of 2018, Swartz Creek was sold to Havenpark Capital Partners, a private investment firm based in Utah. The rent jumped and costly new fees were applied, increasing Hook’s bills by 40%. Havenpark introduced fees residents never paid in the past, including charges for garbage disposal and a school tax, even though residents already paid for sewer, water and schools as part of their county property tax bill.

Hook, 36, lived alone at the time. But with the rent increase, she needed help to pay the bills. “I took on two roommates, so we split the rent into thirds so it’s actually reasonable again,” she said.

Swartz Creek Estates wasn’t the only property purchased by Havenpark, one of many investment companies that moved into the residential real-estate market seeking profits after the 2008 financial crisis.

A year later, Havenpark acquired Golfview Mobile Home Court in North Liberty, Iowa, and immediately announced rent increases that ran as high as 60%.

Golfview residents include young families with children and retired couples who enjoy occasional visits from grandchildren. Yet Havenpark required residents to sign documents agreeing not to place wading pools, swing sets and basketball hoops in their yards.

(Adriana DeRosa/University of Iowa)

“It was crazy stuff, but we had to sign or be evicted,” said 72-year-old Candi Evans, a retiree who has lived in Golfview for 22 years. Evans’ lot rent initially rose from $295 to $405, then $440 in April 2020, and is scheduled to go up to $475 by April 2021.

In late 2019, Havenpark purchased The Highwoods Mobile Home Park in Great Falls, Montana. By then, Havenpark was becoming infamous among some mobile-home residents, who moved quickly to push back.

“I basically wrote to 50 legislators and agencies right off the bat and asked them to please help us since there are no laws in Montana to protect people who rent land,” said Cindy Newman, a Highwoods resident for 20 years. Still, her rent would gradually increase 58% to $450, she said. New tenants pay the full $450 rent.

“When you add the utilities we now pay that used to be included in our rent, that is easily $500 a month from the $283 when they bought our park,” Newman said.

Newman, 67, worries about further increases since she is retired and disabled.

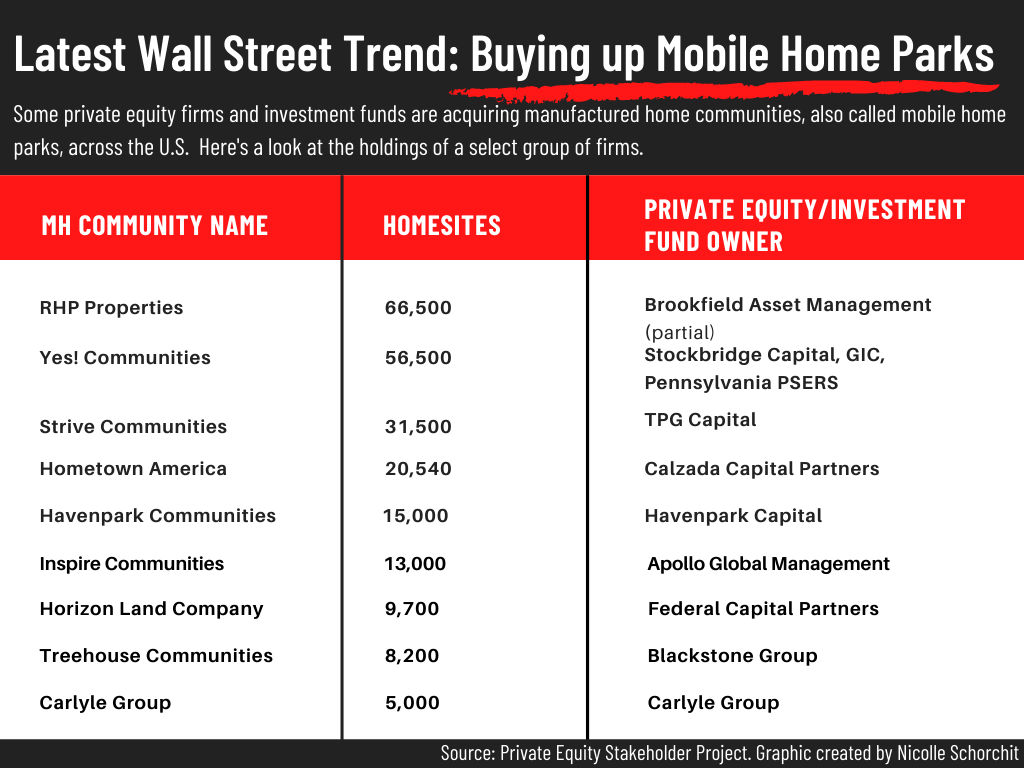

Wall Street-type investment companies, including private equity firms and investment funds, expanded into residential real estate in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, snapping up foreclosed suburban single-family homes at bargain prices and renting them out to middle-class families. The business model has proved so profitable that Wall Street money is now flowing into every segment of the housing market, including mobile home parks and other forms of affordable housing.

The trend creates an unusual juxtaposition where some of Wall Street’s largest investment firms, including Apollo Global Management, The Blackstone Group and Brookfield Asset Management, are now landlords to some of America’s poorest residents. Smaller private investment firms, including Havenpark, have sprung up in recent years with the sole purpose of acquiring large numbers of mobile home communities.

The median household income of a family living in a manufactured housing community is about $35,688 annually, compared to $50,056 for conventional renters and $91,342 for conventional homeowners, according to research by professors Noah J. Durst at Michigan State University and Esther Sullivan at the University of Colorado Denver.

With affordable housing across the U.S. already in limited supply, housing advocates worry big investors are pushing rents up so far so fast that even mobile home communities — the nation’s single largest source of nongovernment-subsidized affordable housing — could become out of reach for families on fixed incomes. The advocates also charge that the investment firms are quicker to evict tenants, especially those who are elderly and on disability, to make room for residents who can afford to pay higher rents.

“Their practice is to drive up profits by gouging residents who are low income or on fixed incomes,” said Elisabeth Voigt, policy and development director at Manufactured Housing Action, a group that’s organizing residents to fight for tenant protections. “Their speculation is destroying affordable housing.”

A spokesman for Havenpark, which now uses the name Havenpark Communities, said the firm’s mission is to preserve affordable housing, not destroy it, by purchasing communities that otherwise might have been sold to developers and replaced entirely with a big-box store or luxury apartment building. That would have resulted in the mass evictions of all residents.

The company said rent increases were necessary to bring rents up to the prevailing market rates while generating enough income to upgrade the properties.

“On occasion, we have purchased communities from operators approaching retirement who have deliberately kept rents low over time,” Havenpark spokesman Josh Weiss said. “While this is typically done out of an altruistic intent, it also has unintended consequences,” such as keeping rents artificially low and receiving too little money to upgrade the properties. He said Havenpark has invested $700,000 in every community it purchased to provide new roads, landscaping and better infrastructure.

Yet the company acknowledges that the hefty rent hikes, which have put Havenpark in the crosshairs of legislators in several states and ignited organized protests from angry residents, may have been too aggressive.

“We had a few communities where we moved too quickly,” Weiss said. In those cases, Havenpark “went back to our residents and announced that the original rent increases would be” spread out over several years.

Private investment funds generally buy properties with the goal of increasing the value, then reselling them at a higher price in the future. Because they tend to have considerable capital, the firms can buy large numbers of properties at a time and pay top dollar for them, outbidding nonprofit housing landlords and resident-owned cooperatives.

Manufactured housing communities, also called mobile home parks or trailer parks, house more than 22 million Americans, according to the Manufactured Housing Institute. The homes are built in factories and are far less expensive than traditional homes, with prices ranging from as little as $10,000 for a smaller, older home to about $200,000 for a newer, larger home. The median price of a traditional single family home in 2019 was $321,500.

About a third of mobile homes are placed in parks where residents often own the home and rent a lot where it’s parked from landlords. Even though lot rents may seem low when compared to apartment rents, mobile-home residents argue they are only paying for a small patch of land. What’s more, they also are making mortgage payments for the mobile home and may pay property taxes and water or sewer bills, unlike apartment tenants.

Yet in many states, mobile-home residents don’t have the same protections as apartment residents from frequent rent increases, retaliation from landlords, lease changes or unfair evictions. In some communities, residents aren’t allowed to form tenant associations or show their homes for resale.

“These people are homeowners and have made a significant investment in an asset that deserves more protections, not less, and yet across the board, they receive less protections than tenants in apartments who don’t have as much at stake,” said Alex Kornya, an attorney at Iowa Legal Aid. In 2019, he said it handled over 700 cases involving disputes between tenants and mobile-home landlords.

The term “mobile” is actually a misnomer since most homes can’t be easily moved after they’ve been parked. Relocating them can cost thousands of dollars, which is out of reach for most low-income residents. This characteristic of mobile-home living, housing advocates argue, is what makes the communities so attractive to investors.

“The way the community owners exploit homeowners’ inability to move is by raising rents and fees knowing that residents can’t move their homes,’’ Voigt said. “And when residents can’t afford the rent or can’t take the harassment anymore or face eviction, they often have no option but to abandon their homes, handing it over to the corporate owner and losing their life savings.’’

In some states, including Iowa, when a resident abandons their mobile home for more than 30 days without reasonable explanation and their rent is three days late during that period, the landlord can claim it and resell or rent it.

Havenpark was founded in 2015 by J. Anthony Antonelli and partners. In 2017, the company wasn’t shy about discussing its business strategy on its website.

“We create value through aggressive optimization programs and lean property management systems,’’ the site said. “Tenant turnover is also minimal since it is difficult and very expensive ($6,000-8,000+) for tenants to move their homes. As a result, operating cash flow is among the highest of any real estate class.”

Havenpark’s current website no longer includes these passages, but the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism viewed archived versions of the website.

One issue housing advocates find especially objectionable is Havenpark has funded its acquisitions at least in part with loans backed by government-controlled mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The two companies, which guarantee about $5 trillion of consumer mortgages, have also been tasked by Congress to help preserve affordable housing by backing loans to the owners of such properties. But the housing advocates argue the agencies shouldn’t help finance private investment companies, which they believe aren’t good stewards of affordable housing.

In mid-November, the housing advocates received a small win when the Federal Housing Finance Agency issued a new rule requiring Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to only back loans to manufactured housing communities that are owned by nonprofits, government agencies, resident-owned cooperatives and private companies that provide better tenant protections.

Before Golfview was acquired by Havenpark, residents said they had a relatively good relationship with the previous owners as long as they “kept a reasonably tidy place, kept the house up in reasonable shape and paid the rent pretty much on time,” said Jean Parker, 70, a resident of Golfview since 1986.

But these days, the relationship between tenants and Havenpark is tense. Parker said shortly after Havenpark took over Golfview, about 20 families departed because they worried they would eventually be priced out if the rent increases continued.

Havenpark put numerous new rules and regulations in place and there were frequent threats of violations over small infractions. If rent was late by a day, a $50 late fee was applied to the bill.

A few months after Havenpark acquired Golfview, Antonelli agreed to attend a one-hour town hall meeting where residents were allowed to air their grievances. The atmosphere was antagonistic. Residents could not bring attorneys or housing advocates to speak on their behalf. Police officers were stationed at the doors.

Evans, who attended, said Antonelli recounted his life story for the first 25 minutes, then rebuffed questions from residents. “It was stupid stuff,” said Evans, vice president of the then-newly founded Golfview Resident Association. “It was a waste of time.’’

Residents subject to eviction or nonrenewal of a lease frequently find themselves struggling to find buyers for their mobile homes. That often results in them selling the homes for below-market prices or, if they can’t find a buyer, leaving the home behind. In some states, including Iowa, an unsold home is considered abandoned and becomes the property of the landlord. Tenants complain this is tantamount to the confiscation of private property; they want landlords to pay market value for the homes.

In 2016, Linda Bates said she received a disability settlement and spent a portion to buy a new mobile home for $62,000. She moved, along with her daughter and granddaughter, to Midwest Country Estates in Waukee, Iowa. After Havenpark purchased Midwest three years later, Bates said she started to bristle at some of the new rules.

Then in late 2019, when it was near the time to renew the lease, Havenpark advised Bates that her lease would not be renewed. She wasn’t given a reason for the eviction, which is called a “no fault” or “no cause” eviction and is legal in Iowa.

“I went into the office, very mad, three or four times and I think that’s why they didn’t renew my lease … because I fought back,” Bates said. Some neighbors said Bates could be unruly at times with them, too — a charge Bates doesn’t dispute.

Her eviction was set for March 15, 2020. At that point, “I had to move or the sheriff was going to come and take me out,” she said. Shortly before the deadline, Bates found a buyer for the mobile home, but he was only willing to pay $22,500, less than half of its value. “I kind of got in desperate times and (the buyer) took advantage.”

Bates, 63, now lives alone in an apartment in DeSoto, Iowa, 15 minutes away from Waukee.

Iowa Legal Aid lawyer Kornya said Bates is “actually one of the lucky ones.” Many residents in similar situations, he said, “end up losing a lot more.”

The Havenpark spokesman said the company can’t discuss a particular resident due to privacy laws. He said they don’t remove tenants “so long as they pay their rent and abide by the agreed-upon community rules.”

But Matt Chapman, a longtime resident of Midwest Country Estates, said “no fault” evictions shouldn’t be allowed. “I don’t understand what a no-fault eviction on a disabled woman … how that is preserving and protecting affordable housing,” said Chapman, who has become a community activist, working with Manufactured Housing Action to push for tenant protections.

The activities of Havenpark and other investment companies have caught the attention of lawmakers, including Iowa State Sen. Zach Wahls, who has introduced legislation to tighten protections for residents.

He said companies like Havenpark “see people’s lives as numbers on the spreadsheet, rather than as neighbors. It is ethically wrong. And the fact that it is legal, to me, is a clear sign that the law needs to change,” Wahls said.

Other tenants complain Havenpark has a practice of giving short notices of upcoming rent hikes. Hook was on vacation with her writers’ group when Havenpark put up the notices two years ago announcing it had purchased the community and promising improvements to the infrastructure. Hook thought it was odd because she felt the complex was already well-maintained.

Two months later, Havenpark announced a new $8 fee for garbage disposal and a $3 school-tax fee. The fees were confusing because residents already paid a fee for garbage pickup and paid school taxes as part of their property taxes.

Havenpark then changed the way residents paid for water and sewer systems. Instead of paying directly to the city, Havenpark became the middleman, installing water meters and charging residents a monthly $5 administrative fee for handling the paperwork. This did not affect the amount residents paid for water but was simply one of the many “fees they tacked on last year in the summer,” Hook said.

In 2019, Havenpark also raised Hook’s community lot rent by another $25. During the fall of 2020, the trash fee increased from $8 to $13 and the chaotic year ended with Hook’s rent going up again by $16.

“It is scary because you don’t know when there’s going to be another notice in your mailbox,” said Hook, the resident in Havenpark’s Swartz Creek Estates in Michigan. “They give you the shortest notice they can get away with legally.”